Veith Kilberth

Skateparks

Designing Spaces for Skateboarding Between Subculture and Sportisation

Abstract

The construction of public skateparks is booming. But how can these building projects, conceptualized to serve their purpose for decades, be designed in a long-term, sustainable manner for dynamic movement practices such as skateboarding? The underlying conflict: These publicly funded skateparks need to serve a maximum number of potential users, but at the same time offer the core target demographic a viable alternative to their free exploration of urban spaces.

The following discourse is an excerpt from a dissertation published by Veith Kilberth that provides actionable concepts for the kinds of sociocultural aspects ideally implemented into skatepark design.

These highly condensed talking points can be perused in their entirety in the referenced sections of Kilberth’s book.

Demand for Skateparks

1. Spatial Conflict

Street skateboarding

Appropriation of public space in early 1990s by skateboarders & inline skaters.

Spatial conflict

Noise, endangerment, damage and trespassing.

Catalogue skateparks

Municipal policy solution creates purpose-built spaces for skateboarding.

Around 1995-2005, planned without user participation, era of pre-fabricated standard-issue skateparks.

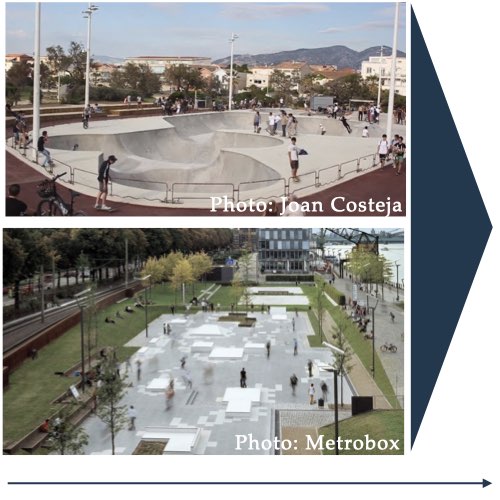

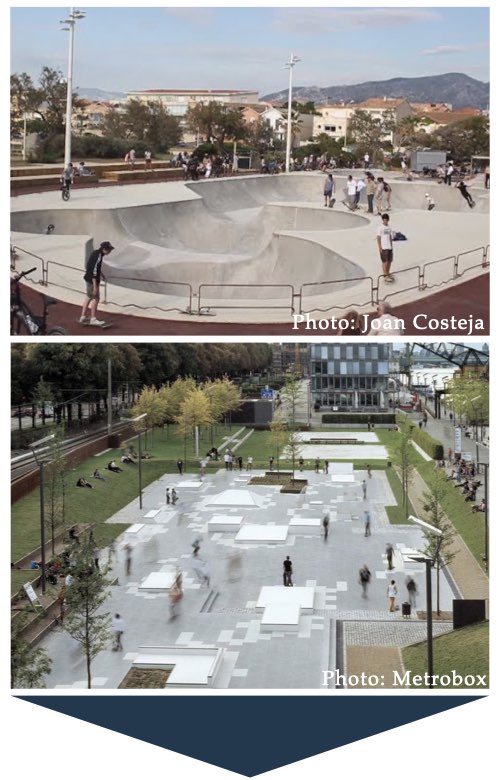

On-site concrete

Skateparks shaped of on-site concrete since approx. 2010, often planned involving end users. Customized, state-of-the-art skateparks.

2. Local Demand

The demand for skateparks is not only driven by spatial conflict, but also by lack of feasible locations in the area (e.g. street spots), as well as local needs and requirements (e.g. transition terrain such as bowls or mini ramps).

Rural regions

Need for transition terrain

Lack of feasible urban spots

1. Spatial Conflict

Street skateboarding

Appropriation of public space in early 1990s by skateboarders & inline skaters.

Spatial conflict

Noise, endangerment, and trespassing.

‘Catalogue’ skateparks

Municipal policy solution creates purpose-built spaces for skateboarding.

Around 1995-2005, planned without user participation, era of standard-issue skateparks.

On-site concrete skateparks

Since approx. 2010, often planned involving end users. Customized, state-of-the-art skateparks.

2. Local Demand

The demand for skateparks is not only driven by spatial conflict, but also by lack of feasible locations in the area (e.g. street spots), as well as local needs and requirements (e.g. transition terrain such as bowls or mini ramps).

Rural regions

Need for transition terrain

Lack of feasible urban spots

Social Aspects

In order to align public skateparks with the common good, they should manifest – at least in principle – a social structure embedded in their design.

1

Largest possible user group

2

Inter-

generationality

3

Inter-

performativity

Social Benefits

Skateparks can offer social benefits on various levels:

Informal

exercise

Safe

spaces

Extracurricular sites of learning

Inter-

generationality

Refugee-

support

Place of retreat for adolescents

Sports for the-

the disabled

Scene

meet-up spot

The Dilemma Behind Skateparks

Alongside the proliferation of public skateparks, the criminalization of skateboarding in public space also increases.

Found spaces

Shared spot

Public sports facility

Private club facility

Degree of domestication & potential for social regulation

Degree of domestication & potential for social regulation

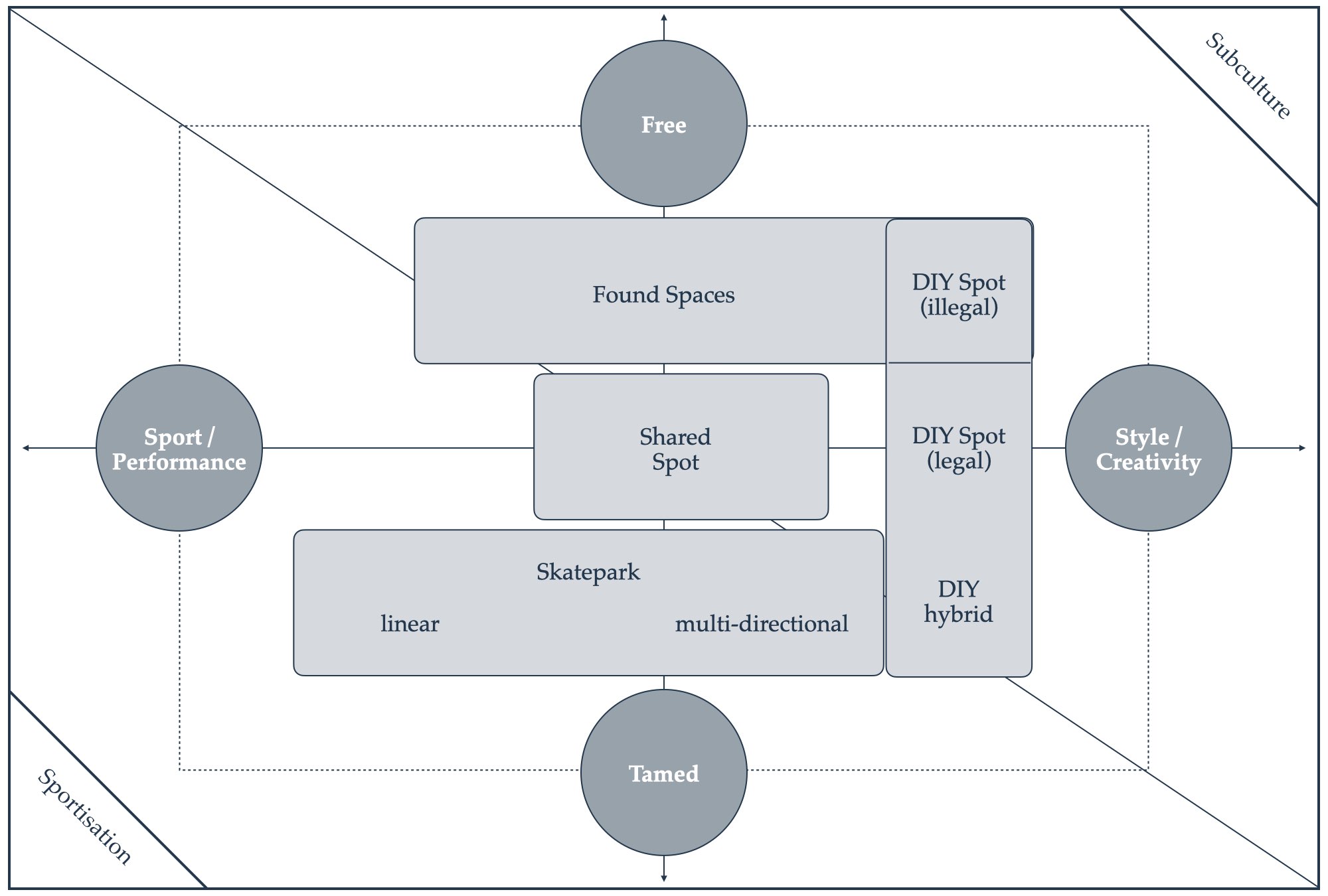

Public skateparks and their underlying domestication of movement practices can unlock the aforementioned social aspects. But these social benefits come at the expense of the free exploration of the city through skateboarding. Solutions are provided by the skate space genesis and the positioning model.

Identity-forming Aspects of Skateboarding

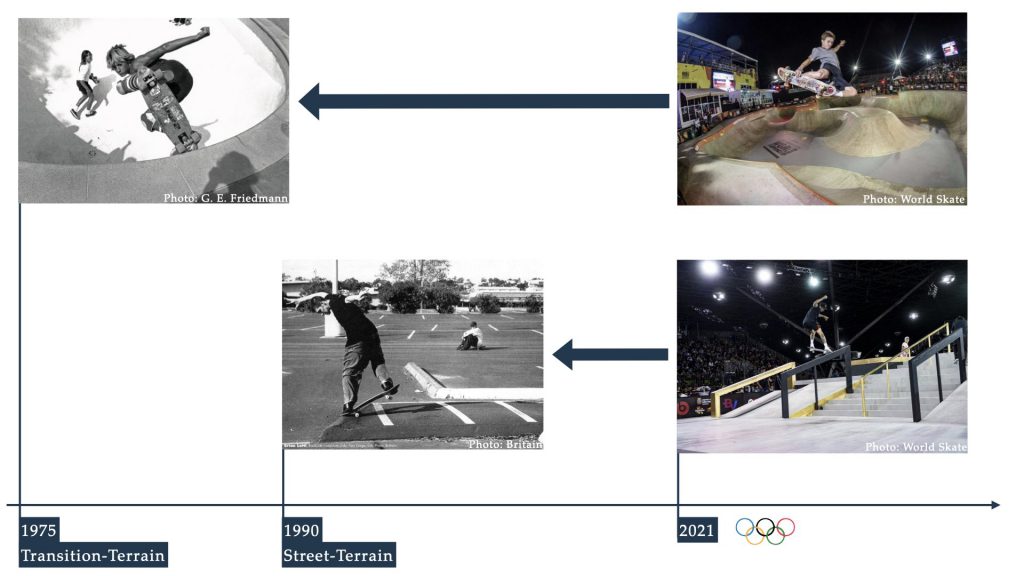

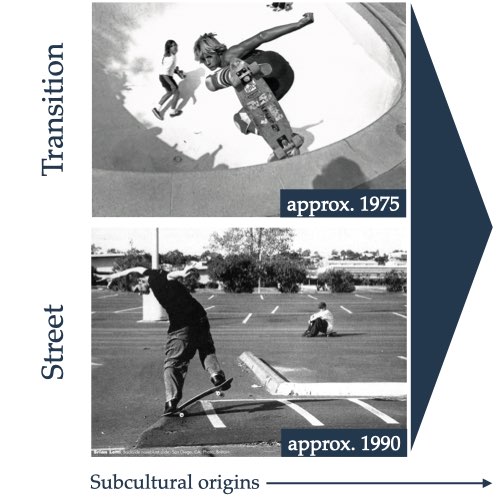

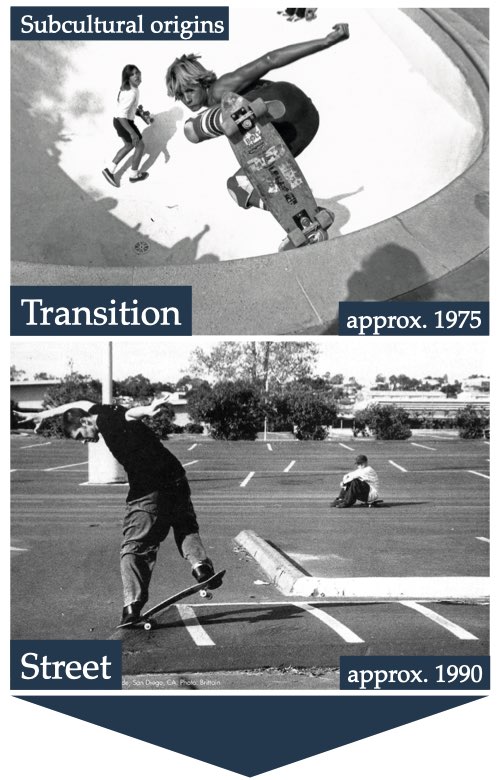

The underlying identity-forming aspects of skateboarding can be outlined via a historic reconstruction of preferred spaces for skateboarding. In the process, the two main terrain categories – transition and street – are analyzed on a micro, meso, and macro level.

Historic Terrain Reconstruction

1

Micro

Perspective

The close-up perspective considers the terrain structure and its elements.

2

Meso

Perspective

The meso perspective, between close-up and panoramic view, is mainly concerned with shifts and trends in terrain preference. For instance when a certain terrain loses value while another receives higher regard by the skate scene.

3

Macro

Perspective

Viewed from the macro perspective, the entire evolution of skate terrain can be interpreted while identifying underlying patterns.

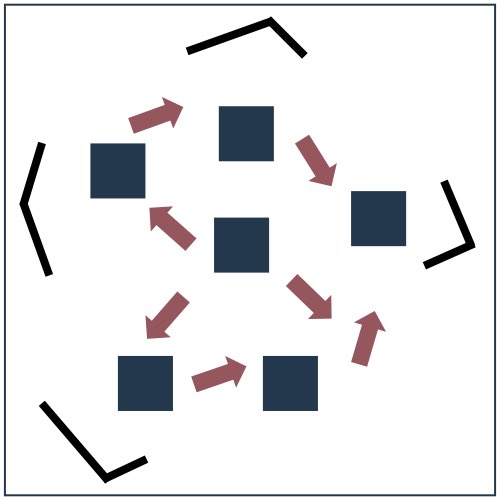

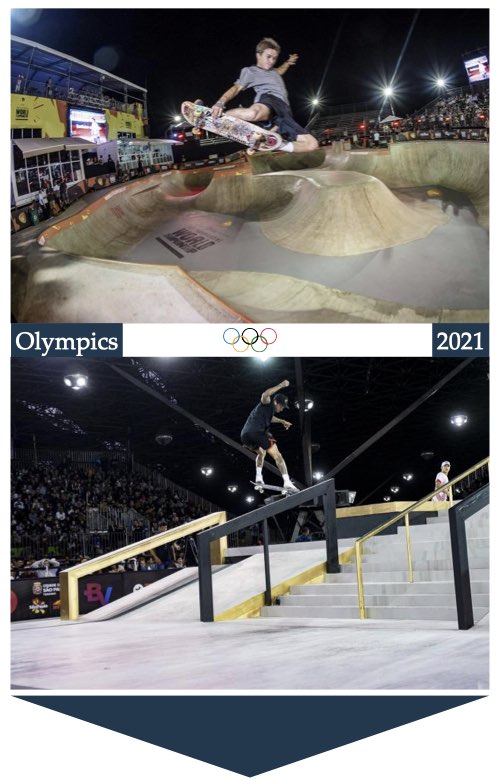

1. Micro Perspective

With a sociology derived from play, as grouped into game categories by Roger Caillois, skateboarding’s spatial structures and constellations can be analyzed on a micro level.

I. Sub Cultural Terrain

Play style: Ilinx (vertigo)

Modus: Paidia (wild, uninhibited play)

Structure: multi-directional

Disposition: creative / style-driven

e.g. Pool, Bowl, Olympic Park

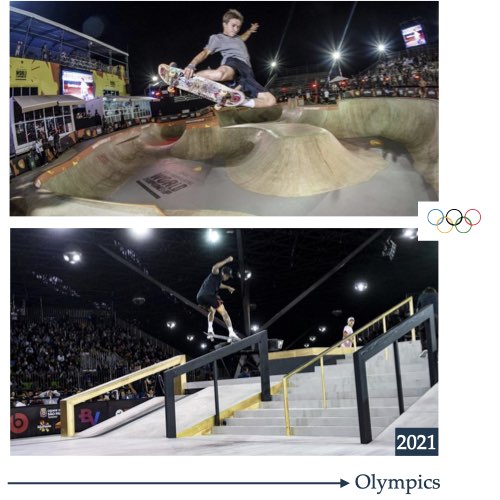

II. Sportified Terrain

Play style: Agon (competition)

Modus: Ludus (disciplined, structured play)

Structure: linear

Disposition: athletic / progressive

e.g. Halfpipe, Miniramp, Olympic Street

The spatial-structural factors behind a sportified mode of play:

1 – Standardized terrain and elements (shape of skatepark components)

2 – Unhindered, linear approaches towards elements, favoring a focus on single tricks (terrain structure)

2. Meso and 3. Macro Perspective

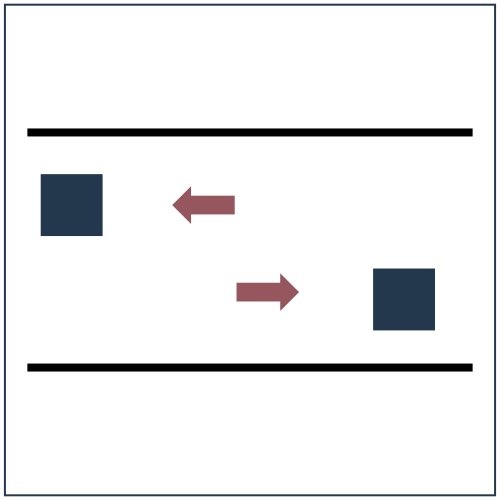

1

Found

spaces

Skate opportunities – Street Spots.

2

Purpose-built

spaces

Public sports facilities – Skateparks.

3

Competition

courses

Commercial events.

Dynamic Terrain Configuration Pattern

A.

Prevailing terrain evolution patterns:

- Found spaces

- Purpose-built terrain

- Competition courses

B.

Self-directed play of bodies in found spaces reconceptualized as externally determined competition formats.

C.

Dynamic process of skateboard terrain configuration, in which the subcultural expression continually reinvents itself.

1

Found spaces

2

Purpose-built spaces

3

Competition courses

Commercial events

Dynamic Terrain Configuration Pattern

A.

Prevailing terrain evolution patterns:

- Found spaces

- Purpose-built terrain

- Competition courses

B.

Self-directed play of bodies in found spaces reconceptualized as externally determined competition formats.

C.

Dynamic process of skateboard terrain configuration, in which the subcultural expression continually reinvents itself.

E.g. the increasing cultural valorization of DIY spaces and more creative approaches to street skateboarding can also be seen as direct responses to the sportisation of skateboarding with event formats such as Street League.

Habitus Thesis: Skateboarding possesses a subcultural identity

Identity Traits of Skateboarding

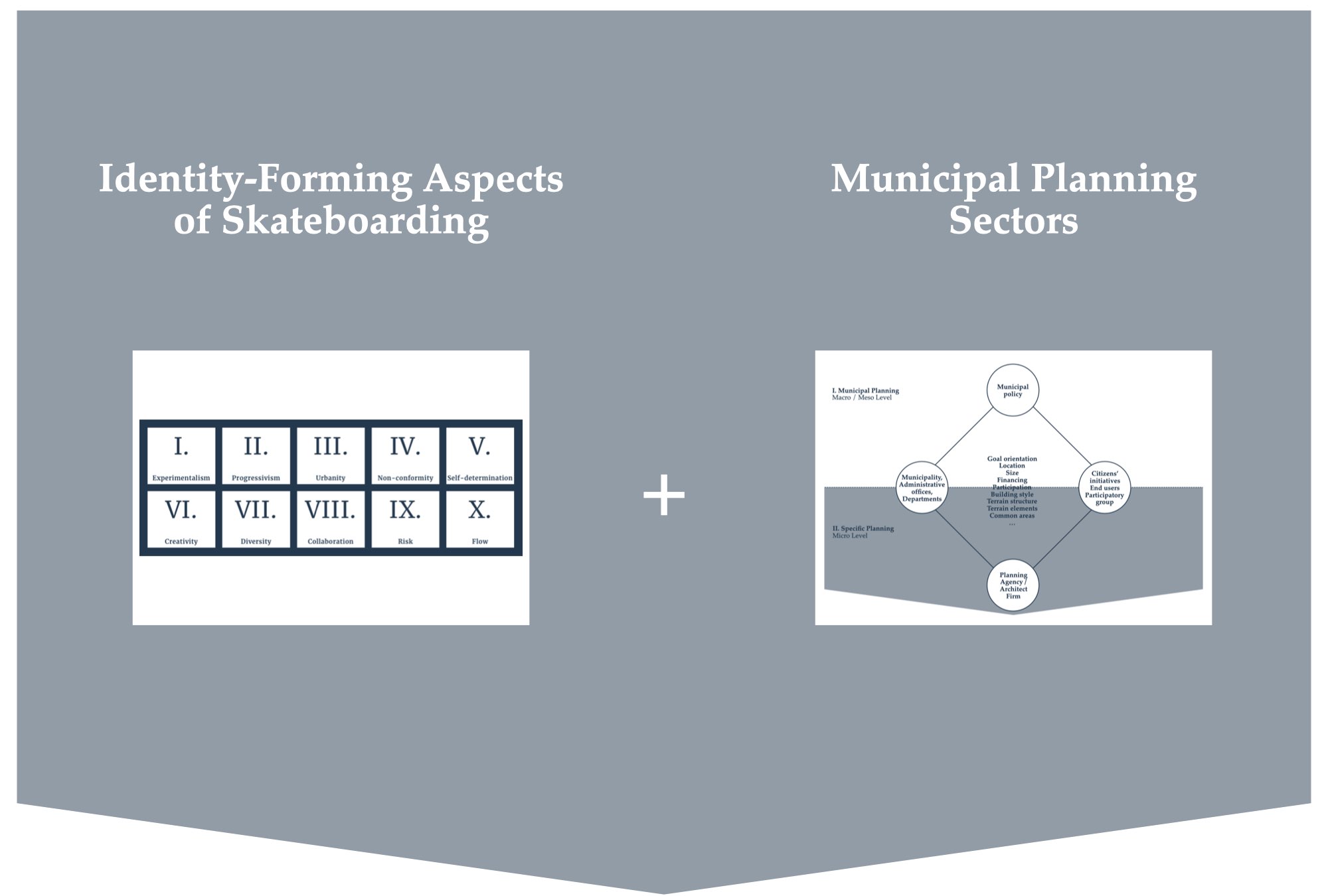

The historical reconstruction of skateboard terrain outlines the following ten identity-forming aspects of skateboarding:

Habitus Thesis:

Skateboarding possesses a subcultural identity

Identity Traits of Skateboarding

The historical reconstruction of skateboard terrain outlines the following ten identity-forming aspects of skateboarding:

I.

VI.

II.

VII.

III.

VIII.

IV.

IX.

V.

X.

I.

II.

III.

IV.

V.

VI.

VII.

VIII.

IX.

X.

The higher the degree to which these characteristics are applied to spaces for skateboarding the deeper the end users will resonate with the space and the greater the chance that the design stand the test of time and remain relevant in the long run.

Concept of fundamental skatepark design aspects

Concept of fundamental skatepark design aspects

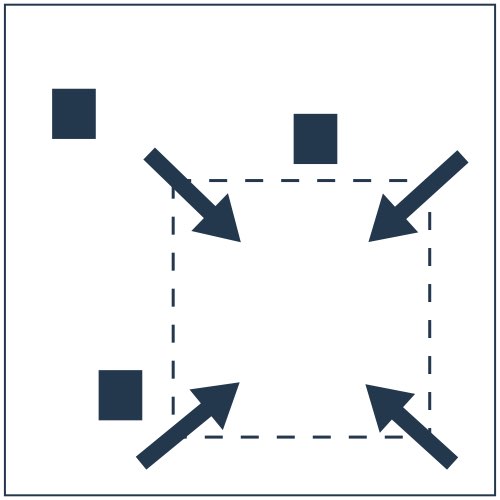

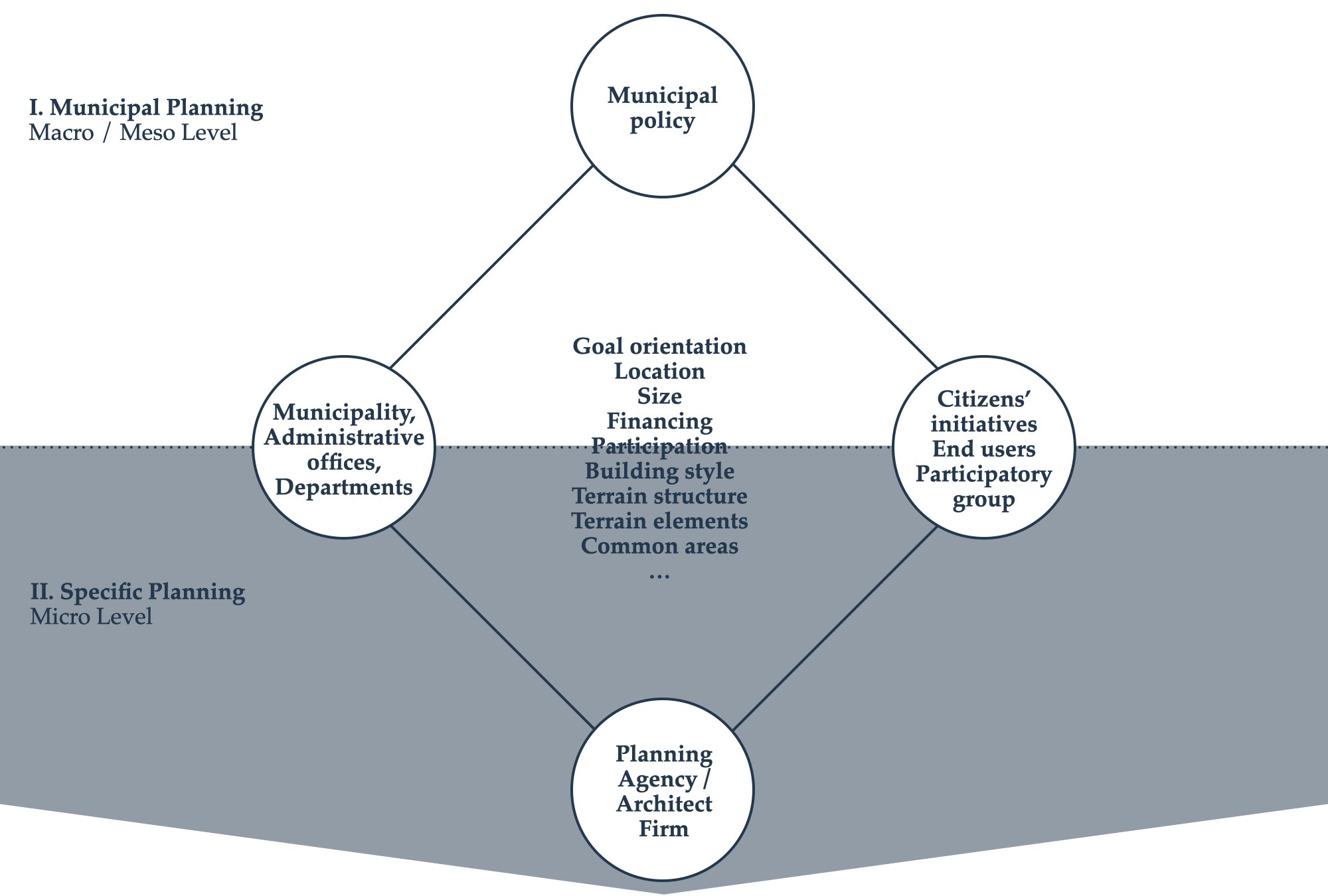

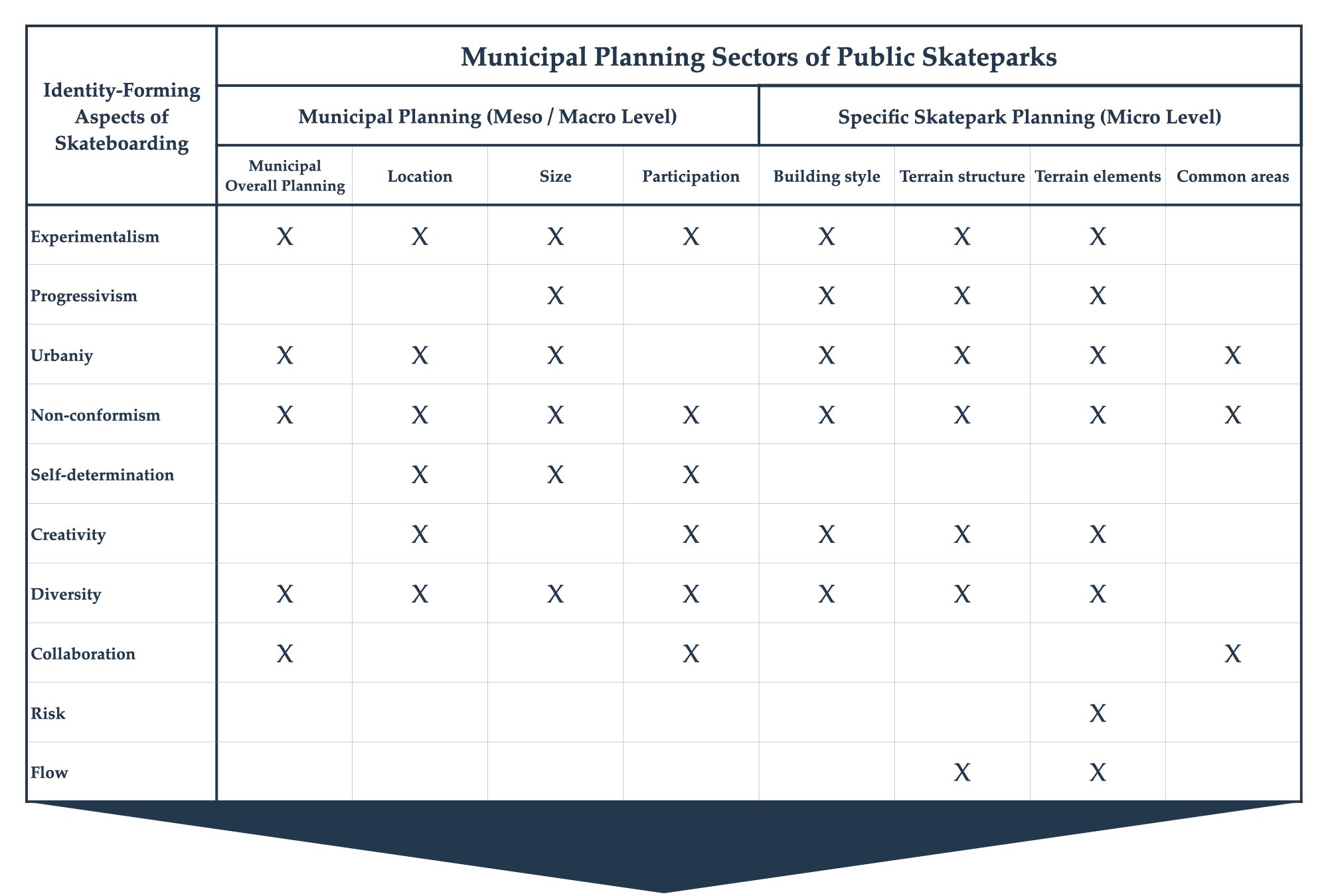

From scientific insights to actionable design guidelines. In order to leverage the identity-forming aspects of skateboarding into spatial concepts, they need to be aligned with planning processes on a municipal and skatepark-specific level:

Municipal and skatepark-specific planning processes:

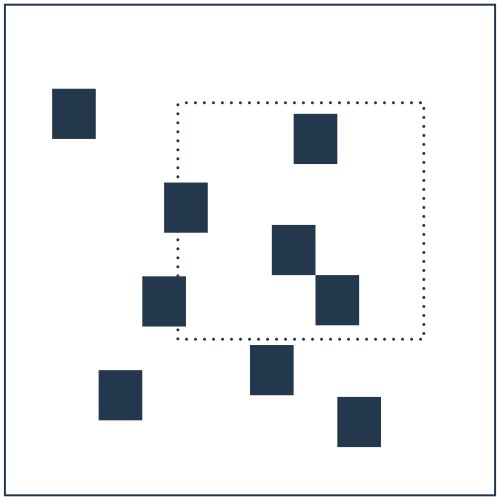

The groups of individuals and organizations involved in municipal skatepark planning, as well as the main planning areas, can be visualized as follows:

In order to define fundamental design guidelines for skateparks, the identity-forming aspects of skateboarding are applied to the previously outlined sectors of municipal planning.

Matrix

23 Fundamental Design Principles

23 Fundamental Design Principles

Municipal Planning Level (Meso / Macro Level)

Municipal Planning

The offering of skateboard spaces is focused on local needs. In turn, every project has to be aligned with the overall offering in the municipality and designed as diversified as possible.

Experimental and non-conformist concepts of skateboard spaces should be considered at the municipal planning level.

Location

Position skateparks in central locations at busy, well visible sites.

When choosing the location, also factor in the maximum number of operating hours.

In addition, consider non-conformist and experimental urban spaces as skateboard locations.

Size

On the regional municipal level, rather plan several relatively small skateboard facilities instead of fewer, larger skateparks.

Make sure not to exceed the maximum size for skatepark terrain.

Participation

Always involve local end users in the planning of skatepark projects and respect their needs and requirements as much as possible.

Create informal, unconventional channels of communication to reach end users and involve them in a participatory planning group.

Skatepark-Specific Planning Level (Micro)

Construction Style

Plan and build state-of-the-art skateparks with the on-site concrete method.

In case of budget limitations, prioritize smaller and higher quality skateparks instead of filling larger spaces with relatively low-quality construction methods and materials.

The ground of a skatepark facility should be crafted from the smoothest, high-quality surface available.

Terrain Structure

Accommodate for different skill levels by structuring areas with different speeds, integrated into the overall terrain structure.

The height and difficulty level within the skatepark terrain should be designed to increase incrementally.

Structure terrains with as many multi-directional pathways as possible.

Avoid a narrow, elongated base area and prefer geometrically proportional, wider spaces.

Terrain Elements

Every skatepark should be designed with a unique character and offer at least one defining characteristic feature.

Street terrains should be planned with a relatively low overall height of elements/obstacles, but also offer more challenging elements.

Skateparks are designed according to skateboarding’s socio-cultural aesthetic and should provide a broad spectrum of different elements/obstacles.

Keep demarcations along the borders of the skatepark space as well as functional safety installations at a minimum in order to create an authentic, urban flair. Use alternative measures to meet safety guidelines.

Start by incorporating a sufficient number of basic skatepark features, then integrate more specialized features.

Common Areas

Plan various common areas in varying proximity to the skate terrain: Always provide common areas in a central location directly at the skate area, but also in peripheral distance with a close view of the action.

Common areas in skateparks should be equipped with authentic, urban furniture found in public spaces in order to avoid the aesthetic of bleachers and ‘sports facilities’.

The Future of Skateparks

The Skateboard Space Genesis

Looking ahead, the proliferation of skateparks could lead, in consecutive phases, to a number of increasingly complex spatial concepts for skateboarding in municipalities:

I. Single Case-Skatepark

State-of-the-art skatepark planned with a high level of end user participation realized as single case project at traditionally zoned sites according to municipality’s overall urban planning directives.

II. Communal Skatepark Offering

Several skatepark projects orchestrated as part of an overall, communal skatepark offering. This second stage of the skateboard space genesis is constituted of separate skatepark projects built at designated sites but integrated into the context of a community-wide offering.

III. Diversified Communal Skatepark Space Concept

In the next step of the evolution, the traditional offering of skateparks planned with end user participation and built at demarcated sites within the municipality is expanded by another dimension: Alternative skatepark concepts, including DIY spaces built by core skaters, are now part of the menu. At the same time, skateboard spaces are appropriated at unconventional sites, such as empty industrial spaces, under bridges, between buildings. These can be opened to development by end users in a self-directed, DIY manner (also including sites used for skateboarding as an intermediate, temporary solution). This third stage of the skateboard space genesis is marked by a heightened degree of involvement by end users, increased planning participation by ‘folks at the ground level’ and, nevertheless, implementation in line with official zoning guidelines in the municipality.

IV. Communal Diversified-Integrated Skate Space Concept

The fourth stage of the skateboard space genesis represents the highest degree of a diversified and integrated concept of skate spaces. Expanding on the previously outlined skateboard spaces, this final stage is concerned with the (re-) integration of skateboarding into the urban realm. The concept of ‘shared spots’ revolves around legalized, purpose-built and legally accepted skate spots that tend to disregard any separation between skate space and urban space entirely. It is only at this stage that a city can claim to have implemented a fully diversified and integrated skateboard space concept.

Skateboard Space Positioning Model

At the intersection between subculture and sportisation, the positioning model outlines a number of opportunities for cities and municipalities to create spaces for skateboarding and urban movement practices beyond conventional skateparks.

*Shared Spot: Multifunctional space for shared use between skateboarders and passerby.

*DIY: Self-made skate spots with a ‘do it yourself’ ethos.

*Found Spaces: Architectural sites in public space that allow for appropriation into skate spots.

*Shared Spot: Multifunctional space for shared use between skateboarders and passerby.

*DIY: Self-made skate spots with a ‘do it yourself’ ethos.

*Found Spaces: Architectural sites in public space that allow for appropriation into skate spots.

Conclusion on the Future of Skateparks

The future of spaces for skateboarding not only lies with designated skateparks, but diversified concepts of spaces for skateboarding that are integrated with value-adding properties into city planning.

About the Author

Veith Kilberth (Dr. phil.)

Former professional skateboarder with a degree in sports sciences and doctorate from the Europa-University Flensburg. Managing partner of skatepark planning agency Landskate and fine lines marketing agency in Cologne, Germany. Current professional and research priorities: Youth marketing, action sports, urban planning, skateparks and skateboarding.

Scientific Publications:

Schwier, J. & Kilberth, V. (2022). Leistungsverständnis und Leistungsentwicklung in bewegungsorientierten Jugendkulturen am Beispiel Skateboarding. In Gissel, N. & Wiesche, D. (Hrsg.), Leistung aus sportpädagogischer Sicht (in Druck). Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Kilberth, V., Mikmak, W. & Isbrecht, S. (2021). Urban Sports-Gesamtkonzept der Stadt Köln 2021. Kommunale Planung von öffentlichen Skate-, BMX- und Parkour-Anlagen (im Erscheinen).

Kilberth, V. (2021). Die Sicht des Skaters. In Tscharn, H. (Hg.) Local Continuum. Köln, Solo.

Kilberth, V. (2021). Skateparks. Räume für Skateboarding zwischen Subkultur und Versportlichung. Bielefeld: transcript.

Kilberth, V. (2019). Soziale Aspekte von Räumen für urbane Bewegungspraktiken im Spannungsfeld zwischen Subkultur und Versportlichung am Beispiel von Skateparks. In Balz, E. & Bindel, T. (Hg.): Sport für den Menschen – sozial verantwortliche Interventionen im Raum. Jahrestagung der dvs-Kommission: Sport und Raum, 2018 in Wuppertal, (S. 147-158). Hamburg: Feldhaus Verlag Edition Czlawina.

Schwier, J. & Kilberth, V. (2019). Quo Vadis Skateboard? In Kilberth, V. & Schwier, J. (eds.), Skateboarding Between Subculture And The Olympics. A Youth Culture Under Pressure from Commercialization And Sportification (p. 7-13). Bielefeld: transcript.

Kilberth, V. (2019). The Olympic Skateboarding Terrain Between Subculture And Sportisation. In Kilberth, V. & Schwier, J. (eds.), Skateboarding Between Subculture And The Olympics. A Youth Culture Under Pressure from Commercialization And Sportification (p. 53-78). Bielefeld: transcript.

Kilberth, V. & Schwier, J. (eds.) (2019). Skateboarding Between Subculture And The Olympics. A Youth Culture Under Pressure from Commercialization And Sportification. Bielefeld: transcript.

Schwier, J. & Kilberth, V. (2018). Quo Vadis Skateboard? In Schwier, J. & Kilberth, V. (Hg.), Skateboarding zwischen Subkultur und Olympia. Eine jugendliche Bewegungskultur im Spannungsfeld von Kommerzialisierung und Versportlichung (S. 7-13). Bielefeld: transcript.

Schwier, J. & Kilberth, V. (Hg.) (2018). Skateboarding zwischen Subkultur und Olympia. Eine jugendliche Bewegungskultur im Spannungsfeld von Kommerzialisierung und Versportlichung. Bielefeld: transcript.

Schwier, J. & Kilberth, V. (2018). Zwischen Vereinnahmung und Unabhängigkeit. In Schüler Wissen für Lehrer. Sport (S. 48-51). Seelze: Friedrich.

Kilberth, V. (2018). Das Olympische Skateboard-Terrain zwischen Subkultur und Versportlichung. In Schwier, J. & Kilberth, V. (Hg.), Skateboarding zwischen Subkultur und Olympia. Eine jugendliche Bewegungskultur im Spannungsfeld von Kommerzialisierung und Versportlichung (S. 57-80). Bielefeld: transcript.

Kilberth, V., Mikmak, W. & Isbrecht, S. (2017). Urban Sports Masterplan Stadt Köln. Köln: Amt für Kinder, Jugend und Familie (unveröffentlicht).

Veith Kilberth (Dr. phil.)

Former professional skateboarder with a degree in sports sciences and doctorate from the Europa University Flensburg. Managing partner of skatepark planning agency Landskate and fine lines marketing agency in Cologne, Germany. Current professional and research priorities: Youth marketing, action sports, urban planning, skateparks and skateboarding.

Scientific Publications:

Schwier, J. & Kilberth, V. (2021). Leistungsverständnis und Leistungsentwicklung in bewegungsorientierten Jugendkulturen am Beispiel Skateboarding (in Bearbeitung).

Kilberth, V., Mikmak, W. & Isbrecht, S. (2021). Urban Sports-Gesamtkonzept der Stadt Köln 2021. Kommunale Planung von öffentlichen Skate-, BMX- und Parkour-Anlagen (im Erscheinen).

Kilberth, V. (2021). Die Sicht des Skaters. In Tscharn, H. (Hg.) Local Continuum. Köln, Solo.

Kilberth, V. (2021). Skateparks. Räume für Skateboarding zwischen Subkultur und Versportlichung. Bielefeld: transcript.

Kilberth, V. (2019). Soziale Aspekte von Räumen für urbane Bewegungspraktiken im Spannungsfeld zwischen Subkultur und Versportlichung am Beispiel von Skateparks. In Balz, E. & Bindel, T. (Hg.): Sport für den Menschen – sozial verantwortliche Interventionen im Raum. Jahrestagung der dvs-Kommission: Sport und Raum, 2018 in Wuppertal, (S. 147-158). Hamburg: Feldhaus Verlag Edition Czlawina.

Schwier, J. & Kilberth, V. (2019). Quo Vadis Skateboard? In Kilberth, V. & Schwier, J. (eds.), Skateboarding Between Subculture And The Olympics. A Youth Culture Under Pressure from Commercialization And Sportification (p. 7-13). Bielefeld: transcript.

Kilberth, V. (2019). The Olympic Skateboarding Terrain Between Subculture And Sportisation. In Kilberth, V. & Schwier, J. (eds.), Skateboarding Between Subculture And The Olympics. A Youth Culture Under Pressure from Commercialization And Sportification (p. 53-78). Bielefeld: transcript.

Kilberth, V. & Schwier, J. (eds.) (2019). Skateboarding Between Subculture And The Olympics. A Youth Culture Under Pressure from Commercialization And Sportification. Bielefeld: transcript.

Schwier, J. & Kilberth, V. (2018). Quo Vadis Skateboard? In Schwier, J. & Kilberth, V. (Hg.), Skateboarding zwischen Subkultur und Olympia. Eine jugendliche Bewegungskultur im Spannungsfeld von Kommerzialisierung und Versportlichung (S. 7-13). Bielefeld: transcript.

Schwier, J. & Kilberth, V. (Hg.) (2018). Skateboarding zwischen Subkultur und Olympia. Eine jugendliche Bewegungskultur im Spannungsfeld von Kommerzialisierung und Versportlichung. Bielefeld: transcript.

Schwier, J. & Kilberth, V. (2018). Zwischen Vereinnahmung und Unabhängigkeit. In Schüler Wissen für Lehrer. Sport (S. 48-51). Seelze: Friedrich.

Kilberth, V. (2018). Das Olympische Skateboard-Terrain zwischen Subkultur und Versportlichung. In Schwier, J. & Kilberth, V. (Hg.), Skateboarding zwischen Subkultur und Olympia. Eine jugendliche Bewegungskultur im Spannungsfeld von Kommerzialisierung und Versportlichung (S. 57-80). Bielefeld: transcript.

Kilberth, V., Mikmak, W. & Isbrecht, S. (2017). Urban Sports Masterplan Stadt Köln. Köln: Amt für Kinder, Jugend und Familie (unveröffentlicht).

*German language only